Data-First Architecture

01 Feb 2018I recently had a light bulb moment when I saw a tweet from Evan Todd. It helped bring together some ideas I have had for a while on software architecture.

Data characteristics excluding software functionality should dictate the system architecture.

The shape, size and rate of change of the data are the most important factors when starting to architect a system. The first thing to do is estimate these characteristics in average and extreme cases.

Functional programming encourages this mindset since the data and functions are kept separate. F# has particular strengths in data-oriented programming.

I am going to make the case with an example. I will argue most asset management systems store and use the wrong data. This limits functionality and increases system complexity.

Traditional Approach

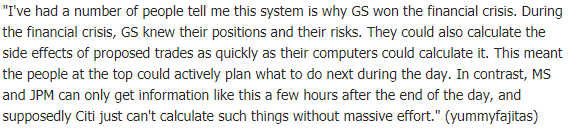

Most asset management systems consider positions, profit and returns to be their primary data.

You can see this as they normally have overnight batch processes that generate and save positions for the next day.

This produces an enormous amount of duplicate data. Databases are large and grow rapidly. What is being saved is essentially a chosen set of calculation results.

Worse is that other processes are built on top of this position data such as adjustments, lock down and fund aggregation.

This architecture comes from not investigating the characteristics of the data first and jumping straight to thinking about system entities and functionality.

Data-First Approach

The primary data for asset management is asset terms, price timeseries and trades.

All other position data are just calculations based on these.

We can ignore these for now and consider caching of calculations at a later stage.

termsdata is complex in structure but relatively small and changes infrequently. Event sourcing works well here for audit and a changing schema.timeseriesdata is simple in structure and can be efficiently compressed down to 10-20% of its original size.tradesdata is a simple list of asset quantity flows from one entity to another. The data is effectively all numeric and fixed size. A ledger style append only structure works well here.

We can use the iShares fund range as an extreme example. They have many funds and trade far more often than most asset managers.

Downloading these funds over a period and focusing on the trade data gives us some useful statistics:

- Total of 280 funds.

- Ranging from 50 to 5000 positions per fund.

- An average of 57 trades per day per fund.

- The average trade values can be stored in less than 128 bytes.

- A fund for 1 year would be around 1.7 MB.

- A fund for 10 years would be around 17 MB.

- 280 funds for 10 years would be around 5 GB.

Now we have a good feel for the data we can start to make some decisions about the architecture.

Given the sizes we can decide to load and cache by whole fund history. This will simplify the code, especially in the data access layer, and give a greater number of profit and return measures that can be offered. Most of these calculations are ideally performed as a single pass through the ordered trades stored in a sensible structure. It turns out with in memory data this requires negligible processing time and can just be done as the screen refreshes.

More advanced functionality can be offered, such as looking at a hierarchy of funds and perform calculations at a parent level, with various degrees of filtering and aggregation. As the data is bitemporal we can easily ask questions such as "what did this report look like previously?" or even "what was responsible for a change in a calculation result?". Since the data is append only we can just update for latest additions and save cloud costs.

Conclusion

By first understanding the data, we can build a system that is simpler, faster, more flexible and cheaper to host.

Software developers cannot always answer questions on the size and characteristics of their system's data. It has been abstracted away from them. People are often surprised that full fund history can be held in memory and queried.

We are not google. Our extreme cases will be easier to estimate. Infinitely scalable by default leads to complexity and poor performance.

With cloud computing, where architectural costs are obvious, right sizing is essential.

Most of the references I could find come from the games industry. I would be interested to hear about any other examples or counterexamples.

References

The One Weird Trick: data first, not code first - Even Todd

Data first, not code first - Hacker News

Practical Examples in Data Oriented Design - Niklas Frykholm

Data-Oriented Design - Noel Llopis

Queues and their lack of mechanical sympathy - Martin Fowler

FAQ - some questions I've been asked

-

How do you deal with previously reported values and make sure they will be the same in the future?

The data model is bitemporal so we can request any reporting data as at any prior time. Lockdown process design becomes simply storing a timestamp for a reporting period. Reporting can make use of lockdown timestamps to produce a complete view of prior period adjustments with full details. Without a bitemporal data model this often becomes a reconciliation process, leading to further manual steps.

-

What about reported values changing due to code changes?

Reporting data can be saved when key reports are generated and used in regression testing. Regression testing of all reports using the old and new code can also be automated. This is very good practice for high quality systems and is not very difficult to implement.